The biblical story of the Exodus—the account of the Israelites’ enslavement in Egypt for 215 years, their massive departure, the 40 years spent wandering the Sinai Peninsula, and their eventual establishment in Canaan—is often regarded by scholars as a fictional event. However, striking evidence may exist in the Sinai Peninsula that challenges this consensus: ancient inscriptions written in the Protosinaitic script.

The Context: Israelites in Bronze Age Egypt

It is a common, though decades-out-of-date, claim that there is no archaeological evidence showing the presence of Israelites or Semitic peoples in Bronze Age Egypt. In reality, the extensive habitation of Egypt by Semitic peoples, particularly in the northern regions, from around 1800 BCE through to the 16th century BCE, is well-established and generally not considered controversial.

Evidence supporting this presence includes a document from Southern Egypt (Thieves) detailing a household of approximately 70 slaves. More than half of these slaves possessed Semitic names, and 11 of those names could be specifically identified as Israelite names based on their similarity to names found in the Bible (for example, the female form of Issachar). The fact that so many Semitic slaves were found in the south suggests that the concentration of Semitic peoples in northern Egypt must have been truly immense.

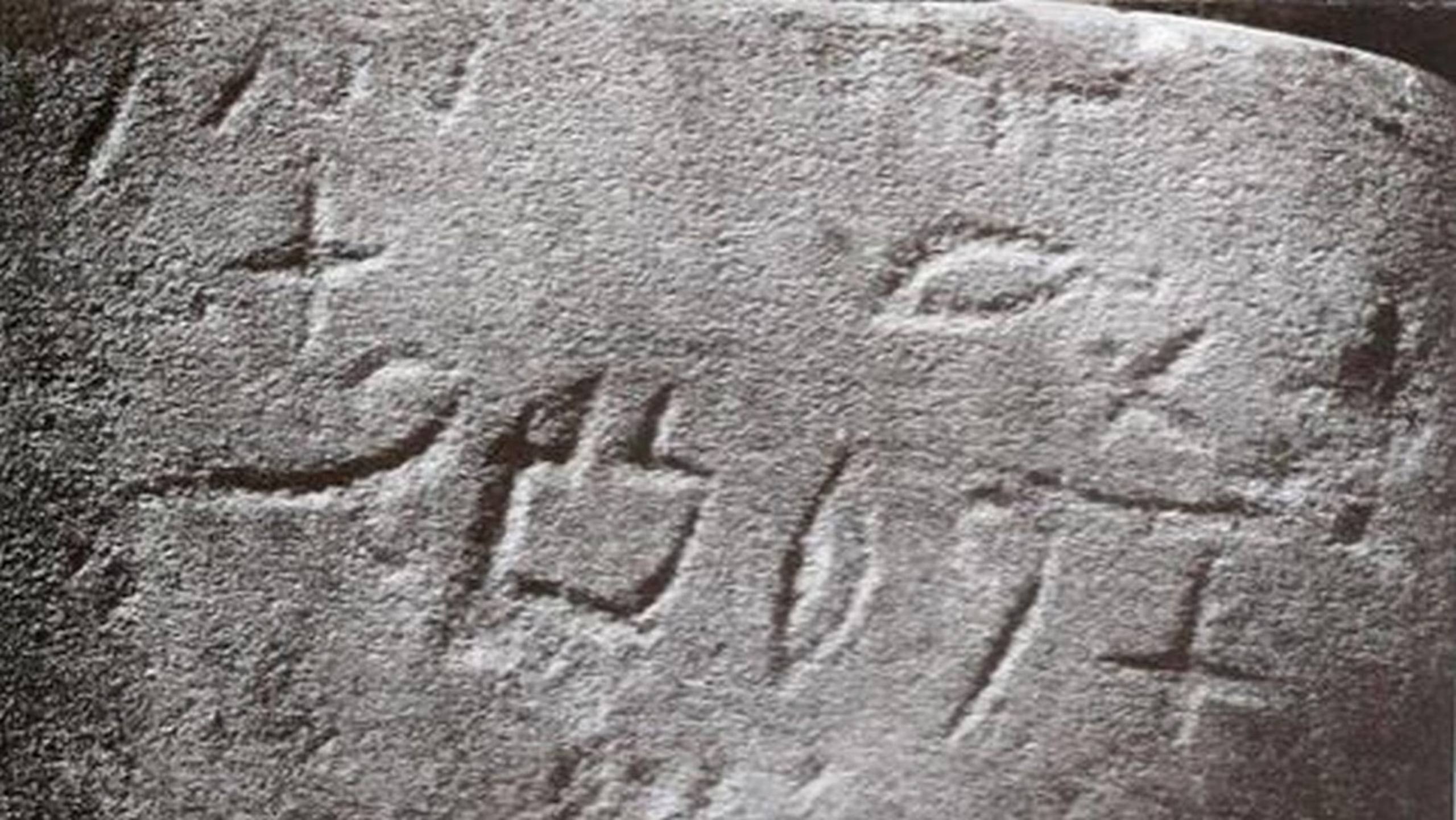

The Protosinaitic Script and the Exodus Route

The Protosinaitic script is key to the potential confirmation of the Exodus. This script appears to have originated in Egypt around 1800 BCE, coinciding with the arrival of these large numbers of Semitic inhabitants. The script itself is an adaptation of Egyptian hieroglyphs, utilized by Semitic speakers (likely Hebrew or a closely related language) to denote the sounds of their language.

The geographical path of this alphabet is highly suggestive, following the supposed route of the Exodus: it begins in Egypt, moves through the Sinai Peninsula, and appears in Canaan, where it later evolved into the script used by the Hebrews and Phoenicians. It is entirely possible that many of the Protosinaitic inscriptions found in the Sinai essentially mark the route taken by the Israelites during their post-Exodus wandering.

The Name of Moses in Inscriptions

Research conducted recently by linguist Michael Baron suggests that some Protosinaitic inscriptions explicitly refer to themes consistent with the Exodus narrative, such as slavery and God providing deliverance.

Even more compellingly, Baron suggests that two specific inscriptions, Sinai 357 and Sinai 361, contain the name Moses. The translation of the expression found in these stones is purported to mean “this is from Moses” or “the declaration of Moses,” a formula similar to expressions commonly used in the Bible.

While there is currently a lack of universal scholarly consensus on these specific translations, the circumstantial evidence strongly supports a connection: the inscriptions are from the right time period, in the right place, and likely written in the right Semitic language.

The Chronological Fit

It is important to note that the potential connection between the Protosinaitic script and the Exodus does not rely on a revised chronology, such as that developed by Egyptologist David Rohl. The established dates for the extensive Semitic occupation of Egypt (c. 1800–16th century BCE) align very closely with the biblical chronology.

The biblical date for the Exodus is 1513 BCE, meaning the Israelite arrival in Egypt would have been around 1737 BCE. These dates correspond well within a hundred years—a matter of decades, not centuries—with the accepted dates for the Semitic presence in Egypt.

The Protosinaitic inscriptions, therefore, are an area of very exciting and recent research that could dramatically shed light on the historical basis of the biblical Exodus story.